On June 25, a district court in California delivered a major decision that added great momentum to the conversations around fair use and the intersection of artificial intelligence with copyright law.

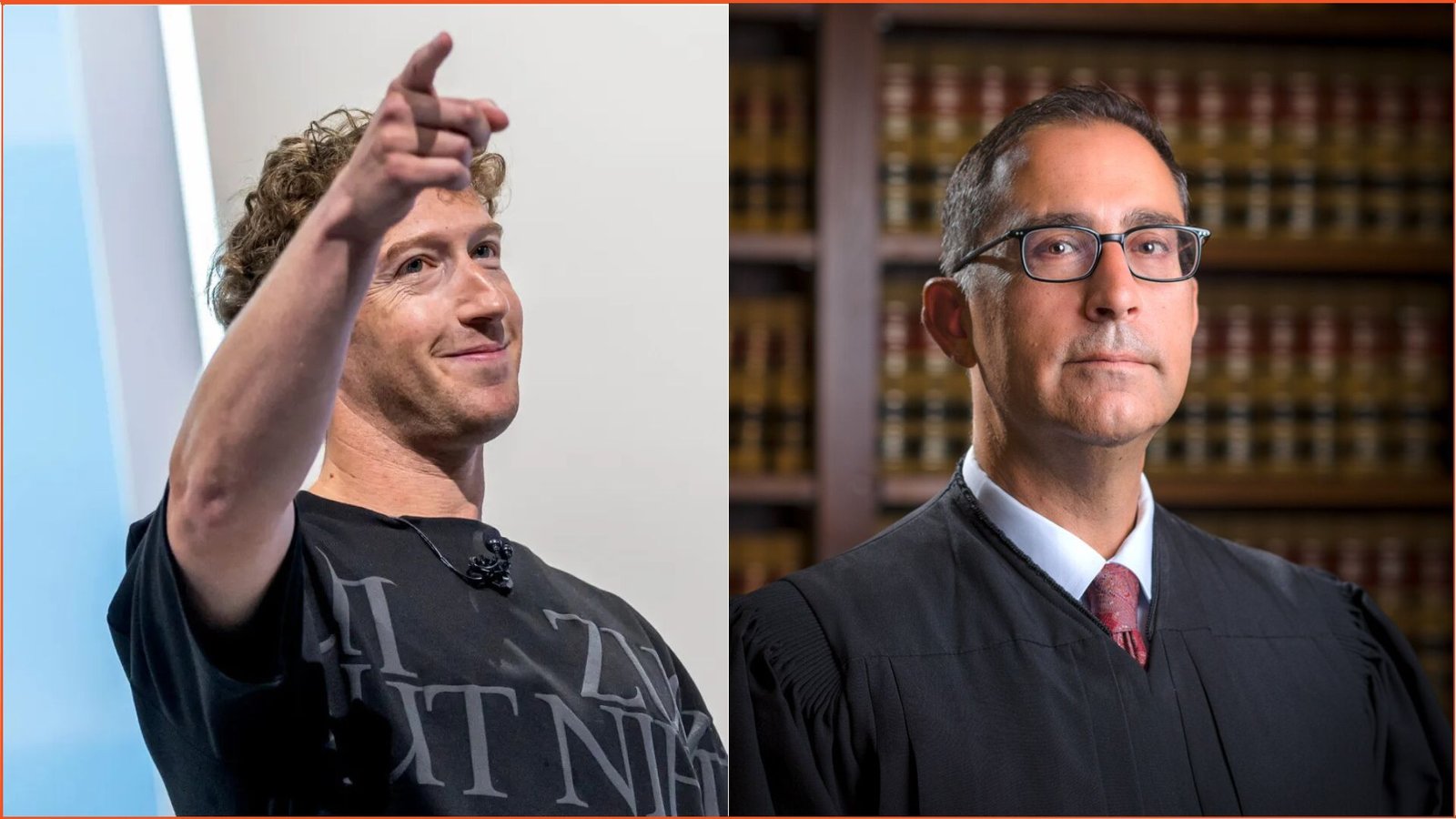

In Kadrey v. Meta Platforms, Inc. (“Meta judgement”), Judge Vince Chhabria ruled that Meta’s use of the plaintiff-authors’ copyrighted works can be considered fair use. Importantly, he recognized the training of AI models as a highly transformative process, one that enables a broad range of new and innovative uses.

This decision, alongside the recent Bartz v. Anthropic judgement (which we covered in a previous article), marks a significant legal victory for AI companies involved in developing large-scale AI models that require this training data.

In this article, Ronin Legal unpacks the Meta judgement and explores its impact on the future of copyright holders’ rights vis-à-vis AI’s rapid advancement.

Background + Decision

The case began in July 2023, when thirteen authors filed a lawsuit against Meta, alleging that the company used pirated copies of their copyrighted works, sourced from rogue online repositories, to train its large language model, LLaMA. The authors argued that Meta’s conduct was exploitative, as it relied on their creative works without permission or compensation.

At first glance, Meta’s actions may seem like a clear case of copyright infringement. However, like many companies facing similar claims, Meta invoked the fair use doctrine; a legal principle that allows limited use of copyrighted material under certain circumstances.

Judge Chhabria ultimately found that Meta’s use of the authors’ works to train its AI model qualified as fair use. However, he was careful to note that this ruling was based solely on the specific evidence presented in this case; it was not a blanket endorsement of all of Meta’s actions.

Fair Use in The Meta Judgement

As we discussed in depth in our previous piece on the Anthropic case, the fair use doctrine provides for four factors on the basis of which courts determine whether the use of the copyrighted work can be considered fair use. In evaluating these factors in the Meta case, the court found the following.

1. Purpose and character of the use

The court held that Meta’s use of the plaintiffs copyrighted works to train its AI model was transformative, as it enabled the model to perform a wide range of functions unrelated to the original purpose of the works. This factor weighed in favour of Meta.

2. Nature of the copyrighted work

The court acknowledged that the plaintiffs’ works were highly creative and expressive, which generally weighs against fair use. Accordingly, this factor weighed in favour of the plaintiffs.

3. Amount and Substantiality

Although Meta used entire works, the court found this level of use to be reasonable and necessary for the purpose of training a language model. This factor weighed in favour of Meta.

4. Effect on the market

The court held that the plaintiffs had not demonstrated sufficient evidence of actual or potential market harm, particularly in relation to licensing markets. This factor weighed in favour of Meta.

How does it differ from the anthropic case?

The Meta judgement arrived just two days after the ruling in the Anthropic case, yet it takes a notably different approach in both tone and reasoning. While Anthropic itself marked a departure from earlier fair use cases, Judge Chhabria’s decision explicitly pushes back on several key points raised in that case.

In Anthropic, Judge William Alsup took a stricter view of the fair use doctrine. He emphasized that the use of pirated or unlawfully obtained works could not be shielded by fair use and treated the legality of the data sources as central to the analysis.

While the court ultimately found that the use of those works for training AI models could qualify as fair use, it did so with caution, placing heavy focus on the need for “clean” data and the illegitimacy of using pirated material.

By contrast, Judge Chhabria acknowledged the questionable legality of the sources used to train LLaMA, but did not treat this as grounds to reject the fair use defence. Instead, he based his ruling more squarely on the evidence presented in court, adopting a broader and more forward-looking interpretation of fair use that took into account the transformative potential of AI technologies.

The Importance of Market Harm

The decisions also diverged sharply in their treatment of the fourth fair use factor. In Anthropic, the court downplayed the potential market impact of AI training, reasoning that since the training data was not publicly accessible, it did not compete in the same market as the authors’ published works.

Judge Alsup even compared the plaintiffs’ concerns to arguing that teaching children to write well might flood the market with competing books.

Judge Chhabria firmly rejected this analogy in the Meta judgement. He stated that “when it comes to market effects, using books to teach children to write is not remotely like using books to create a product that a single individual could employ to generate countless competing works with a minuscule fraction of the time and creativity it would otherwise take.”

The Significance of This Ruling

This ruling is significant for a few different reasons. For one, it sets an important precedent for future cases involving the use of copyrighted material in AI training, particularly where the use is both transformative and potentially market-disruptive.

Additionally, amongst his findings, Judge Chhabria also acknowledged in his decision that training of language models does pose a serious risk of market disruption. In other words, while he ultimately ruled in Meta’s favour in this case, he recognised the broader threat such uses may present to creative industries.

Therefore, unlike the Anthropic case, the court in Meta openly recognized that training large language models may, over time, threaten the market for original works, even as it found such use permissible under current fair use standards.

Conclusion

While the threat of being replaced by AI-generated content is an increasing concern for artists and authors, the Meta judgement made it clear that the plaintiffs’ loss in this case stemmed primarily from a lack of sufficient evidence.

The court emphasized that its decision did not validate all AI uses of copyrighted material; it simply found that the plaintiffs had failed to adequately demonstrate how Meta’s use of their works caused concrete market harm.

Importantly, this leaves the door open for future lawsuits of a similar nature. Artists and creators whose works are used without permission may succeed in court if they can provide strong, fact-based evidence showing that such use impairs their ability to compete, especially where an AI system, trained on their creative output, is used in ways that directly displace or substitute their original work in the marketplace.

Authors: Shantanu Mukherjee, Varun Alase, Akshara Nair